Unveiling the Blood-Stained Reality of Cobalt: From Congo Mines to Canadian Ceramic Artistry

In an era dominated by technological advancement and sustainable energy endeavors, the origins of our materials demand mindful consideration. This deeply came to my attention as I read "Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives," a profound exploration that shattered my preconceptions regarding my cherished glaze ingredient. I didn’t have to delve too deeply to uncover numerous instances of cobalt in my creations. Particularly, the pieces I crafted during my residency at the Banff Centre around 2012, which centered on themes of resource extraction and climate change, align perfectly with the focus of this blog. Despite the escalating costs of mined resources over the past five years and the looming scarcity warnings from our local ceramic warehouses, prevalent awareness and media coverage fail to adequately address this critical topic. Beyond the allure of our smartphones, the promise of eco-friendly electric vehicles, and the elegance of ceramic creations, there now lies a grim narrative of exploitation and anguish. Inspired by Siddharth Kara's illuminating work, lets think about the dark truths of cobalt mining, assess its indispensable role in modern technology, and examine its artistic significance in ceramics.

Understanding Cobalt

“As of 2022, there is no such thing as a clean supply chain of cobalt from the Congo. All cobalt sourced from the DRC is tainted by various degrees of abuse, including slavery, child labor, forced labor, debt bondage, human trafficking, hazardous and toxic working conditions, pathetic wages, injury and death, and incalculable environmental harm.”

― Siddharth Kara, Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives

Cobalt, a rare and essential metal crucial for lithium-ion batteries, primarily originates from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), accounting for approximately 75% of the global supply, with minimal contributions from Canada. Mined predominantly in the Katanga region, the Congo boasts reserves surpassing the rest of the world combined. However, the extraction process lacks the rigorous regulation observed in Canada, rife with human rights violations and environmental degradation. Congolese miners, including children and pregnant women, endure dangerous conditions, earning less than $2.00 a day while facing the hazards of toxic substances, including radioactive elements like uranium. Despite these dire circumstances, the demand for cobalt continues to soar, fueled by the insatiable appetite of the clean energy and tech industry for rechargeable batteries.

The Human Cost of Cobalt Mining

“Cobalt mining is the slave farm perfected. The cost of labor has been nullified through the degradation of Africans at the bottom of an economic chain that purports to exonerate all participants of accountability through a shrewd scheme of obfuscation adorned with hypocritical proclamations about the preservation of human rights. It is a system of absolute exploitation for absolute profit. Cobalt mining is the latest in a long history of “enormous and atrocious” lies that have tormented the people of the Congo.”

― Siddharth Kara, Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives

““Now you understand how people like us work?”

“I believe so.”

“Tell me.”

“You work in horrible conditions and—”

“No! We work in our graves.””

In the heart of the Congo they call the people unregulated mining for colbalt and other materials “artisanal miners”—men, women, and many, many children—plunge into makeshift tunnels, enduring the constant threat of collapse and exposure to hazardous substances. The term 'artisanal' stands in stark contrast to Canadian artisanal ceramic creators. However, unlike ceramic artists, their labor tragically fuels a multi-billion dollar industry, all while they endure poverty and exploitation. Deprived of basic amenities and subjected to exploitation. Sexual assault, inadequate safety measures, and meager wages are the grim realities they face daily, painting a bleak picture of modern-day slavery. In this book we meet the artisanal, small scale miners who dig up the ore and sell it to a middleman for little money. They are men, women, and children who live in stone-age conditions, without local medical care of schools, without protection from the hazardous work. Siddharth Kara traveled to these mine sites and interviewed the workers. They told him that their lives had no value, their deaths counted for nothing..

Unveiling the Supply Chain

“It is tempting to point the finger at local actors as the agents of the carnage---be it corrupt politicians, exploitive cooperatives, unhinged soldiers, or extortionist bosses. The all played their roles, but they were also symptoms of a more malevolent disease: the global economy run amok in Africa. The depravity and indifference unleashed on the children working at Tilwezembe is a direct consequence of a global economic order that preys on the poverty, vulnerability, and devalued humanity of the people who toil at the bottom of global supply chains.”

― Siddharth Kara, Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives

The cobalt supply chain is intricately woven, with various stakeholders turning a blind eye to the atrocities unfolding in the Congo. The Congolese government fails to fund public schools or provide infrastructure, profiting greatly from taxing and embezzling funds from the Congo trade. Mining companies and cooperatives, mostly owned by the Chinese, disregard the working conditions of artisanal miners. Supply chains intermingle cobalt from both industrial "child-labor" free mines and artisanal mines, resulting in widespread exploitation of child labor throughout the industry. Despite claims of ethical sourcing, the reality is far from it, with child labor and human rights abuses pervasive throughout the entire industry. Children are forced into work due to the country's wealth not trickling down to cover the small school fees of $5.00 a month, often necessitating their withdrawal from education to support their families through mining. Protective gear and guidelines for miners are lacking in most mines, exacerbating risks of injury and exposure to toxic materials. Women frequently endure abuse and sexual assault in the mines, except for rare exceptions where protection is provided. The toxic materials released by mining operations pollute surrounding communities, while workers struggle to make ends meet on meager wages, facing short lifespans due to the physically demanding work and high risk of injuries. The tech giants don’t technically own any of the mines and willfully look the other way when the suppliers claim that they are child-labor free. Despite assertions of ethical sourcing, the industry remains tainted by the stark realities of Congolese suffering, exacerbated by the toxic pollution permeating surrounding communities. As the world turns a blind eye, the Congolese endure a systemic web of oppression, orchestrated to remain shrouded in darkness.

A Call for Accountability

“Lasting change is best achieved when the voices of those who are exploited are able to speak for themselves and are heard when they do so.”

― Siddharth Kara, Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives

““Labor is valued by the penny, life hardly at all.””

Kara's poignant narratives underscore the imperative for accountability and systemic reform across corporate and governmental spheres. Profits often eclipse human dignity, perpetuating a cycle of exploitation and suffering. While solutions may appear elusive, empowering the voices of the exploited and dismantling corporate facades offer tangible avenues for change.

Reflections from a Potter's Perspective

I didn’t have to dig deep to find many examples of cobalt in my work, the works created C. 2012 transcended easily to the topic of this blog.

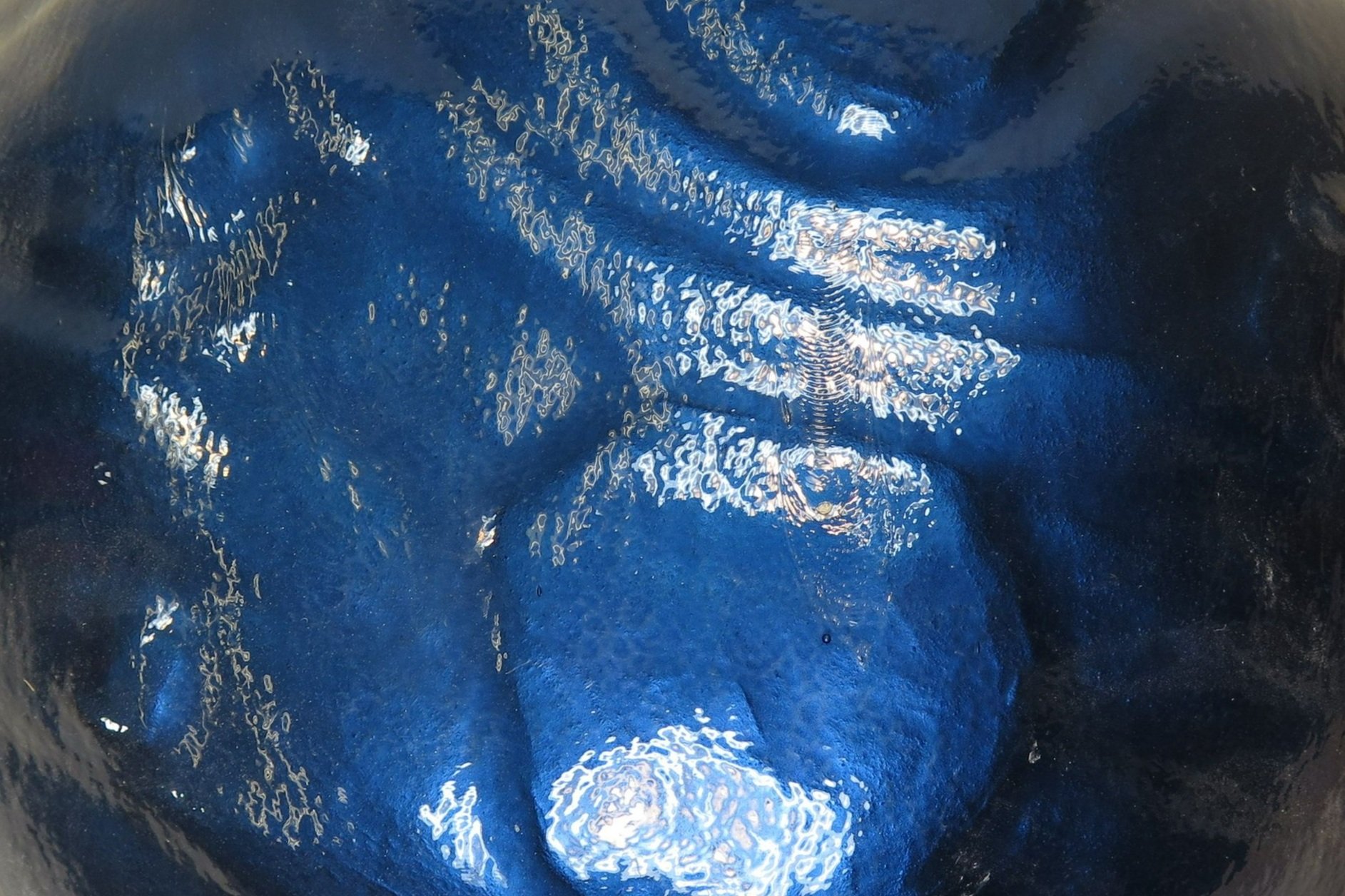

Amidst the shadows cast by cobalt mining, ceramic artistry emerges as a beacon of creative expression. Cobalt oxide, renowned for its vivid blue hue, has permeated pottery since first discovery. From ancient Chinese porcelain to contemporary masterpieces, cobalt's versatility transcends epochs. Yet, today its use in ceramics beckons a critical examination of ethical material sourcing, illuminating broader dilemmas underlying raw material acquisition. As a ceramic artist, I started using cobalt during my early days as a junior guild member at the Fort McMurray Ceramic Guild mixing cone 10 gas fired glazes. Over the years I’ve experimented, dare I say - played - with cobalt as I used it to create the colours, glazes, and textures that I imagined. The piece above uses a shimmery eyeshadow glaze that consists of cobalt, and barium. But as I go from experimenting with glazes to confronting the stark realities of extraction, cobalt's presence in my craft assumes newfound significance. I am no stranger to mining extraction, with roots laying in North American tars ands, Fort McMurray. I have first hand knowledge of extracting resources from the earth ethically and safely and Kara's narrative serves as a sobering reminder, urging a re-evaluation of artistic practices and ethical responsibilities. Ceramic artists can play a pivotal role in promoting ethical sourcing practices by prioritizing Canadian cobalt in their work. By consciously choosing cobalt mined in Canada, artists can contribute to the demand for responsibly sourced materials and support local economies. Other examples such as Jill Rutter's article "Cobalt: suffering for beauty" sheds light on the ethical considerations surrounding cobalt mining and urges artists to prioritize ethically sourced materials in their craft. By joining this conversation and amplifying these voices, ceramic artists can drive positive change within the industry and set a precedent for ethical material sourcing practices.

Support of Ethical Sourcing

“As of 2022, there is no such thing as a clean supply chain of cobalt from the Congo. All cobalt sourced from the DRC is tainted by various degrees of abuse, including slavery, child labor, forced labor, debt bondage, human trafficking, hazardous and toxic working conditions, pathetic wages, injury and death, and incalculable environmental harm.”

― Siddharth Kara, Cobalt Red: How the Blood of the Congo Powers Our Lives

Support for ethically sourced cobalt emanates as a moral imperative to combat human rights abuses and environmental degradation, particularly within the DRC. Canada emerges as a promising source for ethically mined cobalt, offering an alternative to the problematic supply chain in the DRC. In 2022, Canada produced over 3,000 tonnes of cobalt, with notable contributions from provinces such as Ontario, Newfoundland and Labrador, Manitoba, and Quebec. Notably, all of Canada's cobalt production is as a secondary product of nickel mining, reflecting a more sustainable and regulated approach to resource extraction. Furthermore, Canada's cobalt and cobalt product exports were valued at $793.2 million in 2022, highlighting the economic significance of the cobalt industry in the country. With four refineries located in Alberta, Ontario, Manitoba, and Newfoundland and Labrador, Canada has the infrastructure to refine and process cobalt domestically, ensuring greater control over the supply chain and adherence to ethical standards. Ceramic artists can play a pivotal role in promoting ethical sourcing practices by prioritizing Canadian cobalt in their work. By consciously choosing cobalt mined in Canada, artists can contribute to the demand for responsibly sourced materials and support local economies. This not only aligns with ethical principles but also provides assurance to consumers that their artistic creations are ethically and sustainably produced. voices within the artistic community are advocating for ethical sourcing of cobalt.

Agriculture 2014 15”x6”x30” Cone 6 Stoneware, coil built, cast and cold worked glass, flame worked glass. Ciara Jayne Ceramics.

The saga of cobalt transcends mere technological innovation, unfolding as a testament to exploitation, resilience, and ethical awakening. As conscientious consumers, creators, and global citizens, we bear a collective obligation to confront the somber realities pervading our technological marvels. Through heightened awareness, advocacy, and concerted action, we navigate towards a future where progress harmonizes with human dignity. Let us heed the clarion call, for the blood of the Congo stains us all.

Blue water. 2014 10"x10"x2" Slumped Glass Ciara Jayne Ceramics.